This Budget-Friendly, Old-School Planning Tool Could Save Your Vacation This Winter

What will the weather be like — in February of next year? This is the kind of question we often ponder when we're daydreaming about our winter vacation. Will the ski slopes be fully covered in snow? Will the air be so frigid that we won't want to step outside? Should we retreat to the Bahamas, or do we even have to leave the U.S. for white sand beaches and winter escapes? How likely are storms, warm spells, or cold snaps? Even the most far-reaching forecast only predicts weather in 10-day increments, and these often prove inaccurate. How can we possibly plan in September for freezing rain on Valentine's Day?

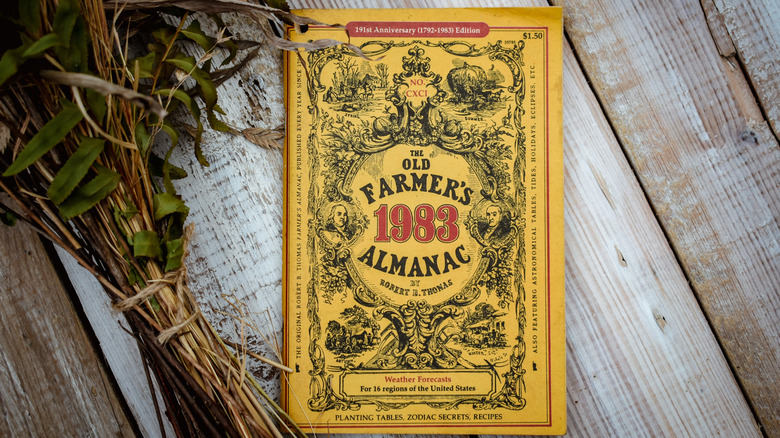

There's one tool that few of us would ever think to use in our vacation planning, something so analog and old-fashioned that we rarely remember it exists. Yet you can find it everywhere, especially in newsstands and supermarkets, where stacks of it wait around for someone to pick up: The Old Farmer's Almanac. This little booklet has been published continuously since 1792, and generations of farmers have planned their plantings and harvests around its timetables for well over two centuries. If you ever spotted that folksy cover and wondered what it was, wonder no longer: The Old Farmer's Almanac comes out every fall and compiles climatic projections for the next 12 months.

While the weather app on your phone might anticipate passing rainstorms next Tuesday, the Almanac makes statements like: "Near normal to slightly milder [temperatures] across much of the country — except in the Appalachians, Southeast, Florida, and the Ohio Valley, where colder-than-average conditions are forecasted." The forecasts are big-picture and far-reaching, less in individual days than in seasons as a whole — which can help you plan your winter vacation a few months in advance.

The story of The Farmer's Almanac

How old is the Old Farmer's Almanac? The first issue was released during George Washington's first term as president. The Almanac was one of the first bestselling publications in the newly formed United States, with 9,000 copies sold in its second year. Much of its content has remained the same: The early Almanac contained tables of astronomical events (such as sunsets) and seasonal changes, and its website claims these predictions were correct about 80% of the time. Since most people in North America worked in agriculture, the Almanac was a valuable resource: Farmers could schedule the best dates to sow seeds for different crops and feel some confidence about forthcoming weather patterns.

The Almanac's founder, Robert B. Thomas, used observations from past years combined with solar science (studying sunspots and solar activity), climatology (prevailing weather patterns), and meteorology (atmospheric changes) to create a secret methodology for predicting the weather. The publication was so popular that a competing version, Farmers' Almanac, was established in 1818, and also remains in print.

The Almanacs are far from perfect, of course. No one could have known that Mt. Tambora would erupt in 1815, coating the atmosphere in smoke and triggering the "Year without a Summer" — though Almanac lore states that the 1816 Old Farmer's Almanac did in fact predict "rain, hail, and snow" for that July. Modern technology and advancements in science have allowed a more modern approach, but even as climate change effects weather predictions and causes hazards like wildfires to become more frequent and more deadly, it can sometimes be useful to have a tool like the Almanac to give you a hint of what your U.S. vacation destination may be like when you plan to visit.

The Almanacs' limits and alternatives

Both almanacs do their best to predict longterm weather patterns, even if their annual reports are often at odds with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Organization (NOAA). If you're planning a ski vacation sometime this winter, the almanacs can give you an idea of where and when you might find the most snow. Trusting any longterm forecast remains an act of faith, and there's always the chance that reality will diverge, but consulting an almanac can give you some hints about the longterm forecast. "I think people appreciate being prepared," Sandi Duncan, an editor of the Farmers' Almanac, told Scientific American. "Even when we're off, they give us a little more leeway."

For general trends, almanacs provide a good amount of solid information, such as tides, sunlight, or lunar phases, which are extremely consistent. These are interesting and potentially helpful, and planting dates are generally reliable for farmers and gardeners. Both almanacs complement these raw data with articles and a jaunty tone. And you can purchase either of the almanacs for about $10, so it won't take much out of your budget.

We do live in the 21st century, though, and you may not want to rely on an old-fashioned periodical that Benjamin Franklin might have kept on his bookshelf. Both almanacs have their websites, which are rich in information and insight. Alternatively, you could type a prospective destination (say, Paris) into an Internet search, then add "monthly weather," "average temperatures each month," or "days of rain each month." You can adjust this search for seasons or snowfall, depending on your concerns. Once you've committed to certain dates, you'll have to take whatever comes. To help, here are 13 ways to predict the weather by watching signs in nature.